In preparation for the Chapter, we have been given rich resources for understanding its goals, such as the syntheses from different areas, videos, discussion guides, and the letters of our Institute leader, Margaret Fielding. The logo addresses us as “women of prophetic hope”, and yet we journey in world-wide uncertainty. “What can we do?” so many ask, and “what is required of us?” I have been asked to write a brief commentary relating a passage from the eighth century prophet Micah to our chapter themes. Micah comes from a strange and different world, and yet his words still resonate. We cannot practice hope unless we recall the loving God with whom this prophet walked, ever in touch with the reciprocity of covenantal love. Like other true prophets of his day, he did not speak for himself but for God. If he were to enter into our conversations on our way, we would realize that he shares our questions and he tells us:

“He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you.”

Micah 6: 8-10

“O mortal,” he might say as he joins us in conversation. It’s not an ice-breaker opening but it shows that he joins us on an equal footing. We are all vulnerable and Micah also has stood helpless at times before the threat of human suffering. Like other prophets, Micah has watched the advance of neighboring empire builders on his people. The Assyrians with great power threaten to devastate the people of Judea. His eyes are open. Those of the people are closed.

What has caused this blindness of a people once faithful to the covenant? Two changes seem to have intertwined to bring it about. They have forgotten justice as they prospered, leaving behind the poor among them whom they continue to exploit. They no longer hear the voices of the hungry and afflicted. Yet more, they have drifted away from their reciprocal relation with God, whose covenant now seems burdensome. They have broken their ties to the covenant that once saved them, trading their hope for what may well be despair.

If Micah were asked in our conversation if the relationship with God can be restored, he would tell us what he told them. He knows that God is steadfast, always here. So, he set up the kind of court case with which the people were familiar. God speaks as plaintiff, revealing their offenses. Yet, God’s words are startling:

“O my people, what have I done to you? In what have I wearied you?”

These are not the words of an angry judge; they sound more like those of spouses, friends, lovers, whose love has been unrequited. It has been said that nothing is so gentle as real strength. God speaks here in the world of vulnerability. Love is active, steadfast and firm even if forgotten. This God offers a path to conversion. The people have forgotten God. “Forgetting”must be healed by “remembering,” by recalling how God has been with them in their past in a relationship beyond their empty rituals. In their remembering they will pray again, in an expression used by Mary Maher in a pre-chapter talk, knowing they pray to “our old friend God”.

Micah reminds us on our way that it’s really all about God. We might share that these words have a familiar ring—these reproaches are repeated as the words of Jesus Christ in the the Good Friday liturgies. It does not de-value their original meaning to say that our hope takes a new shape as it is embodied in the life of Christ.

For Micah, we are all-encompassed by God’s love, a love that might be likened to a three dimensional sphere that no one can step out of. As we grow in realizing our connectedness, we realize that love and justice are intertwined. Micah tells us with a reliable voice that God has heard our questions and God has answered:

He has told you,O mortal, what is good,

And what does the Lord require of you,

But to do justice and to love kindness,

And to walk humbly with your God.

Micah 6: 8

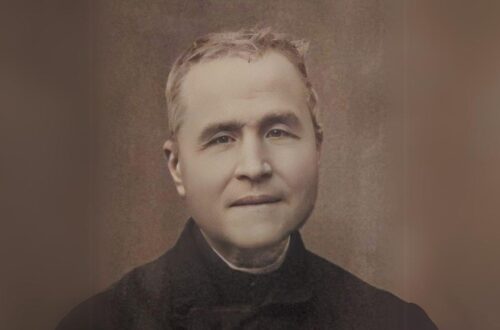

Sister Jacquelyn Porter